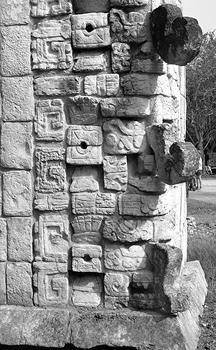

Mayan God Chaac

(Wiki Commons)

|

More

intriguing, however, is the ubiquitous iconographic presence of the

Mayan god "Chaac," god of rain and fecundation. Chaac has a

distinctly

elephantine appearance with a long nose and large, ponderous body. This

deity has been likened to the Hindu elephant deity "Ganesh," although

the two have

somewhat different influences in their respective cultures. Chaac's

nose or trunk, however, appears everywhere (see photo above right) and

has raised the question

of where ancient Mayans might have seen elephants, given that the

Columbian Mammoth is thought to have gone extinct several thoursand

years before the rise of Mesoamerican civilization. It seems

possible, since the Columbian mammoth roamed as far south as Honduras

at the

end of

the last ice age, that tribal memories of these

creatures could have been passed on through oral traditions and

drawings. They

might ultimately have been turned into deities in the Mesoamerican

consciousness. I have seen the well preserved remains of

Columbian Mammoths being unearthed from an ancient sinkhole in South

Dakota. These unfossilized remains, although thousands of years

old, still had

some of the hide intact along with bones and scat. The Yucatan

penninsula is honeycombed with sinkholes (called "cenotes") and

underground streams. These places were virtually the only sources

of

water for the Mayans who explored them extensively. Finding the remains

of Columbian Mammoths in association with their sacred water holes

would have reinforced their ideas about Chaac.

Less likely, although still possible, is the theory

that the Olmecs, Mesoamerica's earliest civilization, were a seafaring

culture that came originally from Africa and brought with them the

concepts of elephants as well as pyramids. These theories will probably

never be either confirmed or disproved, but the extent of

cultural diffusion and Mayan knowledge shouldn't be underestimated.

Contemporary Mayan scholars dismiss the end of the world hysteria that

has been stoked by the popular media in North America. The Mayan

calendar, they say, is simply like the odometer in your automobile,

except that this odometer is attached to the earth as it revolves

around the sun, and the sun revolves around the galactic center. After

so

many miles (and years) it turns over and begins again at zero. There is

nothing special about the end of time in the Mayan calendar they

say. Even so, the locals in Yucatan enjoy the attention it has

brought

them from North Americans who come to explore the ancient ruins, learn

about the Mayans and leave their dollars and pesos. Personally, I find

the Mayan's iconography and architecture distinctive, interesting

and

beautiful, which makes it a good subject for photography.

|